Bandana, un telo quadrato apparentemente semplice, porta con sé una ricca storia e diverse connotazioni culturali, e ha subito numerose evoluzioni in epoche, regioni e gruppi diversi.

Sviluppo: La parola Bandana deriva dal sanscrito "badhnati", che significa "legare" o "legare". Entrò nel dizionario inglese a metà del XVIII secolo. La sua storia iniziò nel subcontinente indiano nel V secolo d.C. Gli artigiani del Gujarat utilizzavano la tecnica di tintura a nodi "Bandhani", che consisteva nell'annodare fili di cotone uno a uno e immergerli in vasche di tintura indaco. Quando venivano slegati, emergevano motivi a pois a forma di stella. Questi foulard quadrati, a cui veniva attribuito il significato di benedizione, erano originariamente simboli sacri per i matrimoni indù. Lo sposo avvolgeva i capelli della sposa con un Bandhani rosso per simboleggiare il legame eterno.

Nel XVII secolo, le navi mercantili della Compagnia delle Indie Orientali portarono questo tessuto a Londra, ma a quel tempo gli inglesi non conoscevano questa tecnica di tintura a nodi e non sapevano pronunciare badhnati, né come definirlo. Fu solo nel XVIII secolo che queste sciarpe quadrate divennero inaspettatamente popolari perché potevano coprire le macchie di tabacco da fiuto, mentre quest'ultimo si diffondeva tra gli aristocratici europei. Venivano approssimativamente traslitterate come "Bandana". Fin dall'inizio del viaggio culturale delle bandane

Nel 1776, quando i coloni misero piede sul continente americano, gli operai tessili di Filadelfia stamparono l'immagine equestre di George Washington e lo slogan "Libertà o morte" sulla bandana, rendendo per la prima volta questo pezzo di stoffa un veicolo di mobilitazione politica.

Negli anni '40, quando "Rosie the Riveter" indossava una bandana rossa per legarsi i lunghi capelli e martellava parti di combattimento sulla catena di montaggio, questo pezzo di stoffa non era più una decorazione, ma una medaglia per le donne che uscivano dalla cucina. Il governo legò deliberatamente la bandana al "lavoro patriottico" per trasformarla da simbolo coloniale a simbolo identitario della classe operaia. Nelle fabbriche automobilistiche di Detroit e nella città siderurgica di Pittsburgh, gli operai usano bandane di diversi colori per distinguere il loro lavoro. I tessuti intrisi di sudore simboleggiano la liberazione di diverse culture artigianali.

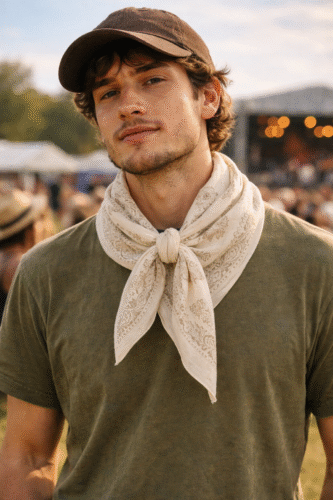

Nel 1967, gli hippy del quartiere Haight-Ashbury di San Francisco trovarono vecchie bandane con motivi paisley nei negozi dell'usato, se le legarono sulla fronte per bloccare le vertigini causate dall'LSD o le legarono al manico della chitarra come dichiarazione contro la guerra. A quel tempo, la bandana non era più un oggetto pratico, ma un simbolo di rottura con la cultura sociale dominante dell'epoca. Quando le madri della classe media vedevano i loro figli avvolgersi i lunghi capelli con le bandane, era come vedere l'ordine culturale tradizionale crollare tra le pieghe di una sciarpa quadrata.

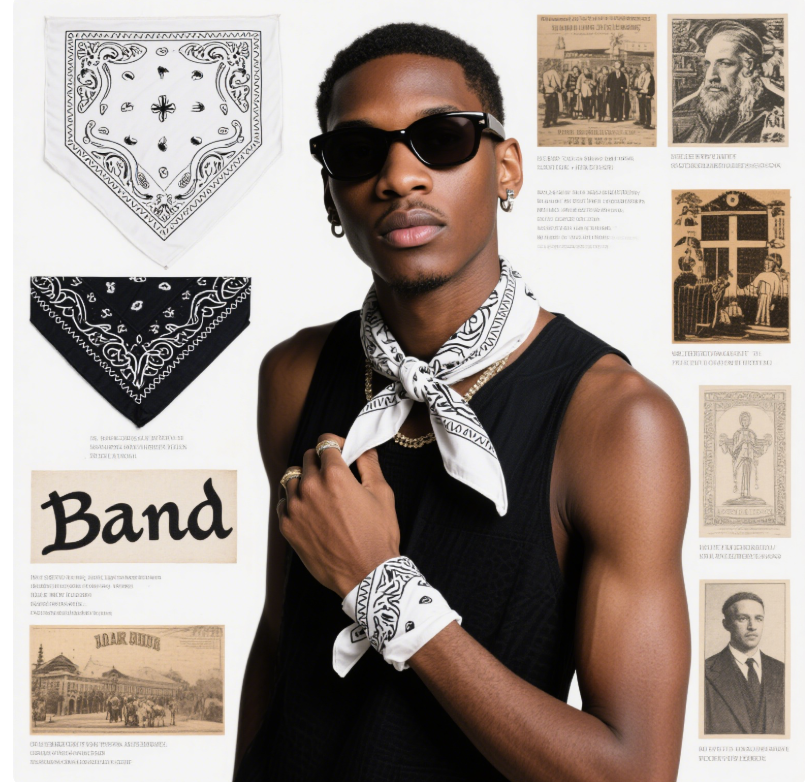

Nelle strade della California meridionale degli anni '80, la gang dei Bloods si fasciava i polsi con bandane rosse, mentre quella dei Crips si annodava sciarpe blu intorno alla vita. I due colori divennero simboli di vita e di morte nelle risse di strada. In seguito, il rapper Eazy-E si coprì il volto con una bandana nel video musicale "Boyz-n-the-Hood", sfumando i confini tra gang di strada e cultura hip-hop. Da allora, questo pezzo di stoffa ha assunto un duplice significato: rappresenta le gang dei bassifondi ed è un simbolo della vita alla moda in studio di registrazione.

Dopo un periodo di evoluzione, solo nel 2018 le bandane hanno inaugurato la loro evoluzione più significativa. Le modelle hanno sfilato indossando veli in stile bandana stampati con il logo della doppia G, che hanno elevato la bandana da simbolo della cultura street a simbolo della cultura della moda. Ironicamente, quando Louis Vuitton ha stampato il Monogram sulla bandana, i prodotti artigianali un tempo colonizzati sono ora diventati trofei culturali dell'impero del lusso.

Ma la vitalità della bandana non si fermerà mai sul palcoscenico dell'alta moda. In Medio Oriente, i palestinesi usano la "Kefiah" a scacchi bianchi e neri (essenzialmente la versione araba della bandana) per protestare contro l'occupazione israeliana, trasformando questo pezzo di stoffa in una bandiera di liberazione nazionale. In Giappone, i giovani di Harajuku si legano la bandana al collo, creando uno stile "City Boy" a metà tra retrò e futuro. Durante l'epidemia, quando le mascherine sono diventate una necessità globale, innumerevoli persone hanno ripiegato la bandana come dispositivo di protezione temporaneo: è tornata al punto di partenza, rispondendo alla crisi del momento con la più primitiva praticità.

Eevoluzione storica delle bandane È il prodotto di una collisione storica di quel periodo e, in una certa misura, rappresenta lo status quo storico di quel periodo. Un tempo le era stato attribuito un significato religioso, politico e un simbolo della cultura di strada, per poi essere sbiancato dall'industria della moda e riapparso sulla scena della moda. Quando oggi leghiamo questa sciarpa quadrata ai polsi o al collo, tocchiamo con mano non solo la morbidezza del cotone, ma anche il calore e i segni lasciati sul tessuto da innumerevoli mani negli ultimi cinque secoli.